At 03:30 on July 6th 1922, beneath a Nordic sunrise, a wooden crate was eased open on the banks of a Swedish backwater. Two Eurasian beavers slipped into the current and vanished downstream. The tiny audience held its breath. For the first time in decades, Sweden had beavers again.

Sweden had only just realised what it had lost. The country’s medieval place-names are strewn with bjur and bäver, proof that beavers were once woven into everyday life; yet relentless demand for pelts and castoreum drove the species to national extinction by the 1870s. A ban on beaver hunting arrived in 1873 – two years too late. The shock of losing a species so thoroughly Scandinavian stirred an early conservation conscience. Writer Pehr Arvid Säve mocked the ban as “locking the stable after the horse has bolted” and immediately proposed bringing beavers back. That idea simmered for nearly half a century until Eric Festin, curator of the Jämtland County Museum, decided to act.

Festin was no rich philanthropist. He sold subscription certificates at country fairs, persuaded city merchants to match rural donations and used his own salary to close the funding gap. His motive was not to restock a game species, but as he wrote to “restore our devastated fauna” and prove that Swedes could mend what Swedes had broken. Norwegian trappers captured a healthy pair from one of the few remaining relict populations on the lower River Glomma; a postal rail wagon carried them north; and a rattling cart hauled them the last miles along forest tracks to the River Bjurälven.

Hunter-naturalist Axel Sylvén, who helped Festin rally support, captured the mood in a fundraising letter:

“May we, however, hope for success for the endeavor and live to see the day when the beaver has reinhabited its old homes, which now for a whole century have stood empty and abandoned, only a reminder of where human folly and predatory lust can lead – a reminder perhaps necessary in the present time, when other species of wildlife are also seriously threatened by the same, of the beavers’ sad fate.”

Within seventeen years Sweden had repeated that moment at 19 sites. Fast-forward from that 1922 dawn to today’s 2025 anniversary and roughly four human generations – or nearly twelve beaver generations – have come and gone. In that time the Swedish population has increased to 130,000 and beavers now cruise beneath Stockholm’s commuter bridges little more than a kilometre from the Royal Palace.

A century-long continental head-start

Sweden’s release marked the beginning of a remarkable roll-out across Europe. The Czech lands had quietly welcomed beavers back in the early nineteenth century. During the 1920s and 1930s Norway, Latvia, Russia, Finland and Germany followed. The 1940s and 1950s added Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Switzerland, Estonia, France and even Mongolia. Kazakhstan joined in the 1960s; Austria in the 1970s; Hungary and the Netherlands in the 1980s; Slovakia, Croatia, Belgium, Romania and Denmark in the 1990s; and the early 2000s saw Serbia, Spain and Bosnia and Herzegovina restore their own populations.

Britain, by contrast, waited until 2009 for a trial wild release in Scotland and until 2016 for England’s first licensed wild population on the River Otter. Legal protection finally reached Scotland in 2019 and England in 2022 – three to six beaver generations behind much of Europe, precisely the lag Sylvén warned against.

Expert insight from Sweden

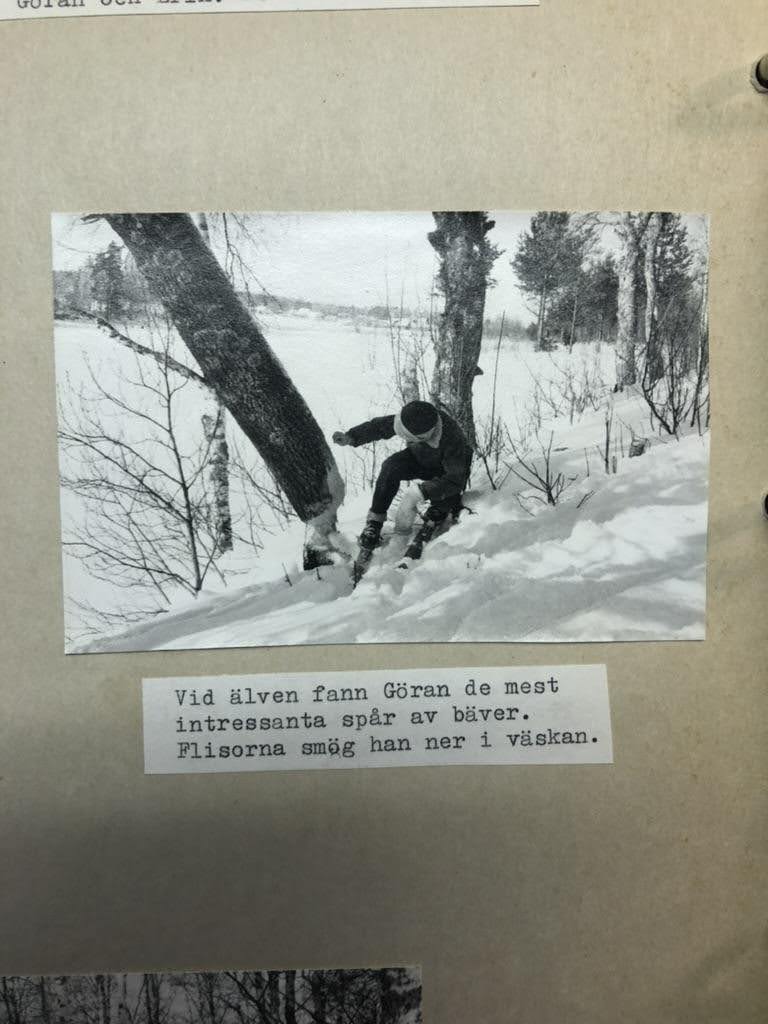

“in February 1968, I had seen a beaver felled tree for the first time (see picture below). I still have the chip of wood I collected.”

Over the next four decades, Swedish ecologist Göran Hartman would devote his career to Castor fiber. His reflections on Sweden’s beaver revival read like a practical field manual for Britain, now embarking on its own restoration journey:

“When beavers first come to an area, landowners are at first positive to have a new and interesting species on their lands. When trees start to fall and ditches are dammed up they start complaining about this new nuisance species. After a while they get used to the presence of beavers and consider them as natural as roe deer and foxes. Be patient.”

Sweden’s population has rebounded to more than 130,000 animals, from Stockholm’s city canals to the forests of Jämtland. Yet even this success carries conflict, Hartman notes:

“A current challenge is that people still have not learned to be proactive instead of reactive. If there are beavers in a watershed and there are trees that you value, then put metal nets around them before the beavers fell them. If there are road culverts in a stream where there are beavers, build so called beaver deceivers or similar devices, before the beavers clog the culverts. It has been difficult to make people understand this. It should come as naturally as fencing in your chickens to keep them safe from foxes and hawks or protecting planted trees and bushes from being browsed by deer.”

As Scotland, England and Wales take early steps toward beaver re-establishment, Hartman offers further guidance:

“Be aware that there might be problems with balancing different views on beavers, beavers as a conservation object, as cute and cuddly animals, as a nuisance species, as a game species etc. I see all these views as valid. This not only a question about different groups in the society, it is also a question of time. The ultimate goal of a reintroduction is that the population should increase to a level where it becomes a common species that is of no need of special protection. If the views on the species do not change in accordance with the population development it will result in tensions and bad decisions.

Teach people the different techniques there are how to avoid beaver problems. Shooting beavers is often just a short-term solution. There will be new beavers coming. Do not neglect the problems beavers may cause but at the same time you must inform people about the benefits of having beavers in your watersheds.”

More than a century after Swedish biologist Axel Sylvén expressed his hope that beavers might “re-inhabit their old homes,” we asked Hartman whether that vision has been realised 103 years on:

“Absolutely. We are now almost there as there are still some suitable parts of the country that are not yet colonised. Thinking of how the reintroductions were carried out, i.e. releasing small propagules and not a thought about possible inbreeding depression, it is rather remarkable that it worked.”

And what unsolved question still keeps him curious?

“The most expensive, laborious, time consuming and cause of shifting between sadness and joy, project was my attempt to study exploratory dispersal. I wanted to know what subadults had seen and chosen from on their tour between their natal territory and where they set up a territory of their own. This was supposed to be solved by attaching radio transmitters to young beavers and then track them from the ground, from canoe and fixed wing aircraft. I did not get enough data to make much of it. All it resulted in was a little short communication about dispersing one-year old beavers. I learned a lot but I still don’t know much about exploratory dispersal in beavers.”

Debunking the “no room” myth

Sceptics still insist that modern Britain is too crowded, too farmed or too engineered for beavers. Yet across Europe the species thrives in places at least as busy as our own. In the intensively cultivated Netherlands 3,000 to 4,000 beavers descend from just forty-two animals released in 1988. In Vienna they share cycle paths along the Danube Island with morning joggers, and in Stockholm they build bank dens within sight of city-centre office blocks. At the wilder end of the spectrum, beavers flourish in the headwaters of the Carpathians and in the last fragments of primeval forest at Białowieża.

Their secret is adaptability. Beavers feed on more than three hundred plant species, switching from willow and aspen to water-plants and grasses. They excavate burrows where watercourses are deep enough, construct lodges where they are not, and build dams only when they need to raise the water. This behavioural toolkit lets them settle everywhere from alpine torrents to sea-level agricultural areas. Britain’s river network, with its mild winters and comparatively abundant riparian willow to some countries, offers them a relatively gentle landing. What we lack is not habitat but the desire to live alongside them.

A moment of choice

A century after Festin’s beavers paddled into Bjurälven, Britain needs to face up to the overdue restoration of a species that can aid wetland creation, river restoration, freshwater biodiversity, natural flood management, drought resilience and the simple joy of watching wildlife at the water’s edge.

The question is no longer whether beavers can live in our landscapes, Europe answered that decades ago, but whether we will let them, and whether we will share in the benefits they engineer for free.

On this anniversary it seems fitting to echo Sylvén’s hope, updated for our own era: May we live to see the day when the beaver has reinhabited its old homes across Britain – before another generation passes us by.

You can read more about the beaver’s journey back to Sweden here.